How to Design a Flowchart (+ Creative Flowchart Design Ideas)

Flowcharts are powerful tools for simplifying complex processes by illustrating them in visual form. Today, we’ll show you how to design a flowchart, without having to install or invest in any premium software.

Whether it’s to map out a business process, plan a project, or break down a concept, a well-designed flowchart goes a long way to enhance communication. However, crafting a flowchart that is both informative and engaging requires creative and strategic thinking.

To remedy that, we also found a few creative flowchart design ideas to help you find inspiration for your flowchart designs.

Let’s get started.

2 Million+ Digital Assets, With Unlimited Downloads

Get unlimited downloads of 2 million+ design resources, themes, templates, photos, graphics and more. Envato Elements starts at $16 per month, and is the best creative subscription we've ever seen.

What is a Flowchart?

A flowchart is a visual representation of a process. It’s commonly used by businesses, schools, startups, and various other fields mainly to showcase more complex systems and processes in a simple way.

For example, many businesses and startups use flowcharts that represent the different stages of product development, allowing anyone to easily understand the steps and procedures involved in the process.

Why Use Them?

The main purpose of a flowchart design is to present information in a way that makes it easier for people to understand more difficult systems and processes, even when they are not familiar with a topic.

This leads to a better understanding of systems and finding flaws, problems, bottlenecks, and inefficiencies more easily. As a result, flowcharts play a key role in troubleshooting and business development.

Creative Flowchart Design Ideas

Flowcharts used to be dull. Back in the day, they only had squares, circles, and triangles. But now, flowcharts come in many different styles and designs. Here are a few of those cool and creative flowchart design ideas for your inspiration.

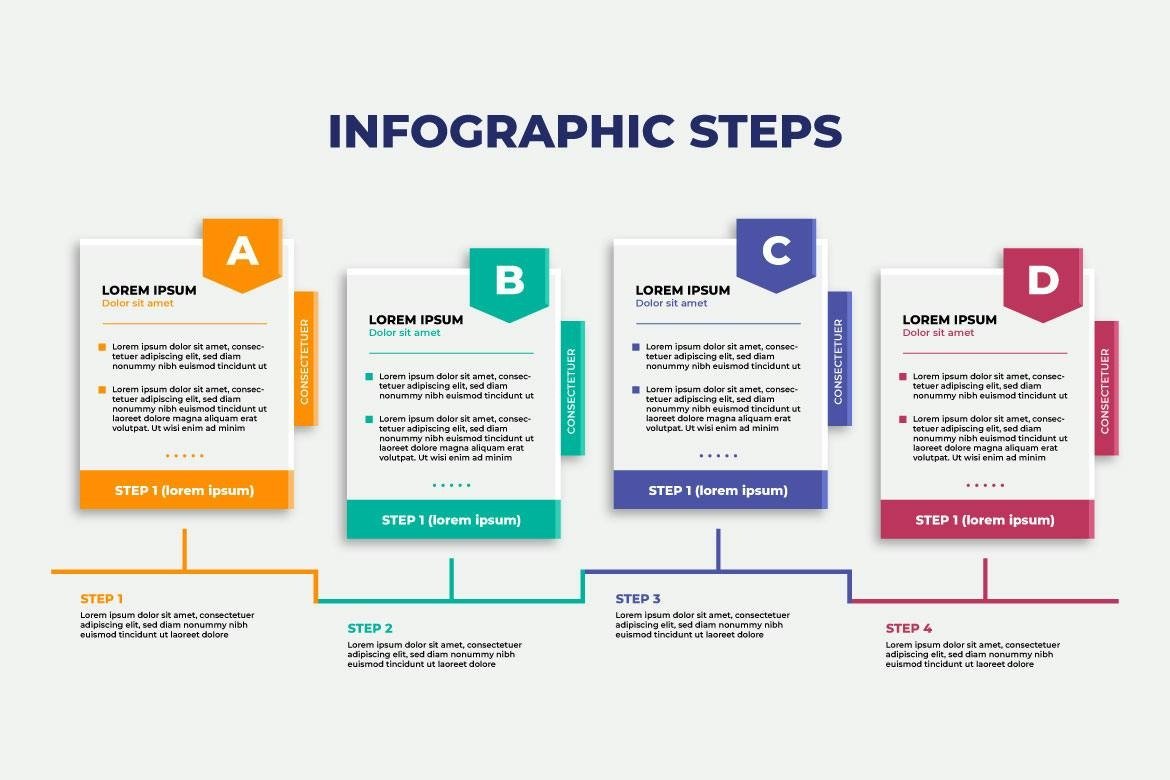

Infographic-Style Flowchart

Infographic flowcharts are much more useful in education and information-related flowchart designs. They combine elements from infographic designs with flowchart layouts to convey information more effectively.

This style of flowchart uses lots of visual elements, such as icons, illustrations, colors, and different fonts, to offer a more visual-centric experience to the users.

Timeline Flowchart

Timeline flowcharts also have an infographic-like design but they are more effective in streamlining time-related flowchart layouts, like project roadmaps, campaigns, and product development.

Timeline flowcharts often have simple horizontal layouts and they are much easier to create. But they can also be as complex as you want.

Color-Coded Flowchart

One of the most commonly used and popular types of flowchart is the color-coded flowchart design. By using different colors to represent different types of information, these flowcharts make it much easier to grasp information. And they are much prettier as well.

Color-coded flowcharts are ideal for projects that tackle multiple subjects, stages, or even different departments of a business. They are also great for organizing information into one simple design.

Loop Flowchart

Loop-style flowcharts are perfect for showcasing repetitive and recurring processes in visual form. They also make flowchart designs look much more creative with circular layouts, rather than the traditional horizontal and vertical designs.

Arrow Flowchart

Arrow flowchart designs come in handy when it comes to showcasing the steps involved in projects, campaigns, and progress. Arrow flowcharts are not always horizontal, they can also be warped to create circular, infographic, roadmap, and many other styles of flowchart layouts as well.

Lightbulb Flowchart

Lightbulb-style flowcharts take inspiration from the popular diagram and infographic designs of the same concept. These flowcharts are especially suitable for flowcharts related to startups, ideation, and concepts.

Roadmap Flowchart

Roadmap flowcharts are similar to timeline flowchart designs, except this style of flowcharts uses a design that stays true to its name.

The roadmap design of these flowcharts will allow you to showcase your project roadmaps and product launch plans in a more entertaining way.

Minimal Flowchart

If you prefer to use only a few visuals, icons, illustrations, and colors in your designs, this is the ideal style of flowchart design for you.

Minimal flowchart designs use fewer design elements or minimal-themed icons and objects to create a more professional look to your flowchart designs.

How to Design a Flowchart

As you know, there are so many different styles of flowchart designs out there. While we can’t show you how to design them all, we’ll walk you through a very simple process of creating a basic flowchart. And you can follow the process to create other types of flowcharts.

Choose a Software

There are many different software and tools you can use to design flowcharts. Some of the popular options include graphic editing tools like Photoshop, Illustrator, Affinity and Designer. And you can also use UX design tools like Figma, Sketch, and Adobe XD. As well as presentation tools like PowerPoint and Google Slides.

We’ll leave it up to you to choose the software that you’re most comfortable with.

Step 1: Create a Blank Figma Whiteboard

For this tutorial, we’re using Figma to create a simple flowchart. Figma is free to use and you can access it from your browser on any platform. No installation is required!

Let’s start by creating a blank Whiteboard in Figma, which is available on the new FigJam platform.

Step 2: Create a Flowchart with AI

FigJam has an impressive AI assistant that allows you to create various types of diagrams, flowcharts, and designs with text prompts.

You can use this AI assistant to easily create any flowchart design within seconds.

Simply type what sort of flowchart design you want to create in the Generate box and it will give you a few different options to choose from.

Step 3: Or Use Templates

Or, you can use a template to quickly design a flowchart. For this, select the “Start with a template” option below the AI generation box.

Then search for flowchart templates and pick a template to get started.

Step 4: Customize the Flowchart

After choosing a template design, you can start customizing the flowchart to change colors, text, and layout to your preference.

Step 4: Export or Publish

Once you’re done with the flowchart design, you can easily share it with your colleagues or teammates.

You can also export the flowchart in JPG, PNG, and PDF formats.

In Conclusion

There are many different ways you can design flowcharts these days using different software like PowerPoint, Word, Photoshop, Sketch, and more.

You can find flowchart templates for all these apps and more on Envato Elements. Using a template is the easiest and most effortless way to craft professional-looking flowchart designs.