Figma to WordPress: Tips, Tools & Advice

Making your own WordPress themes used to be a complex process that only the most skilled web developers were able to do. But, when using Figma, this process becomes just as simple as setting up a WordPress website.

One of the most powerful features of Figma is its third-party plugin support. There’s so much you can do with them, including the ability to convert your designs into fully functional WordPress themes without even having to write code.

Today, we take a closer look at the process of taking your designs from Figma to WordPress and see how it works. We also lined up some useful tips, suggestions, and a quick guide on how to get started.

Let’s dive in.

2 Million+ Digital Assets, With Unlimited Downloads

Get unlimited downloads of 2 million+ design resources, themes, templates, photos, graphics and more. Envato Elements starts at $16 per month, and is the best creative subscription we've ever seen.

Figma to WordPress: How It Works

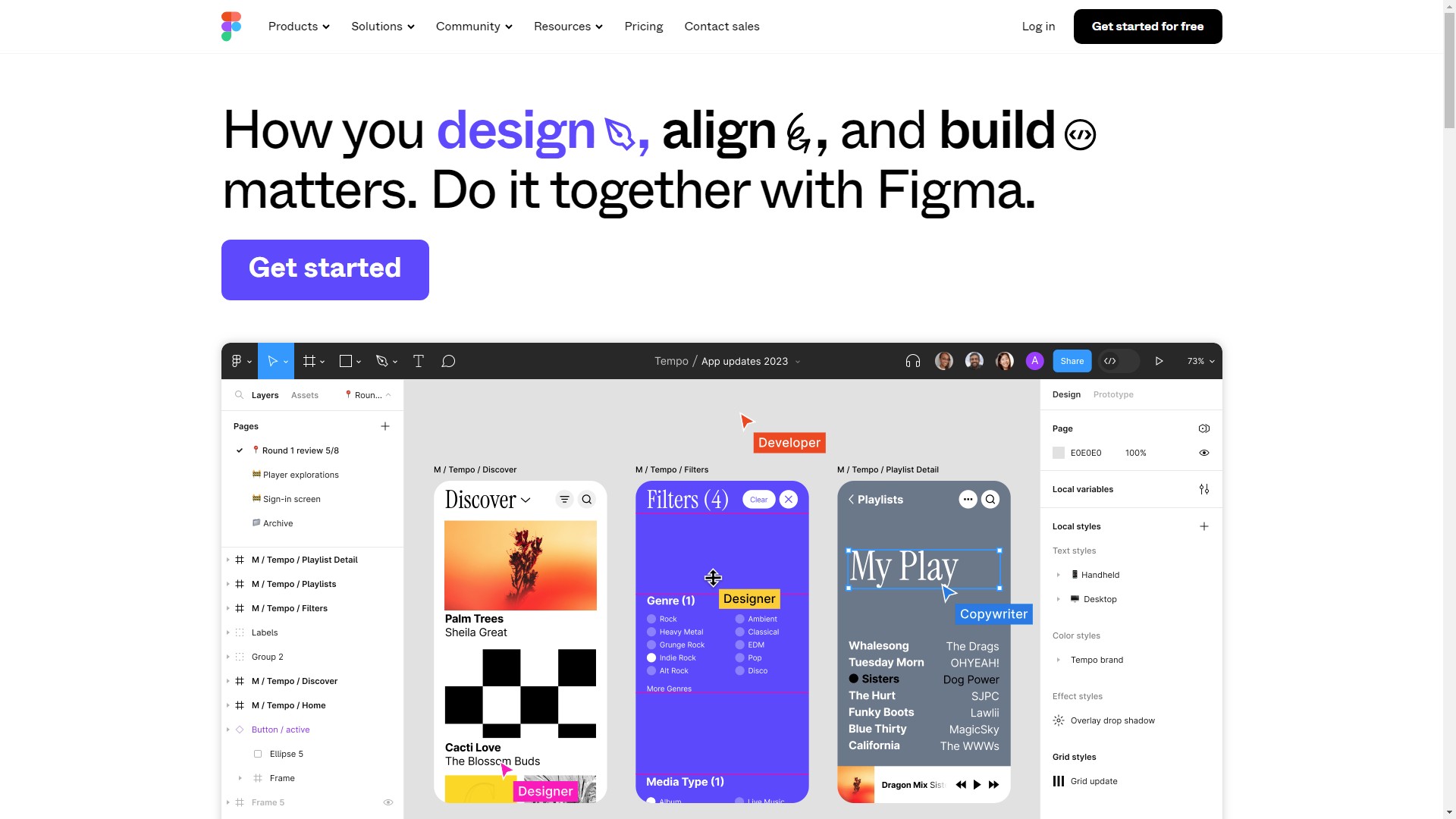

Figma is a tool mainly used to design websites and app user interfaces. After designing a website using Figma, you normally hand it over to a web developer to convert the design into a functional website. Or, if you’re a full-stack developer, you’ll have to write the code to create the website.

With Figma plugins, you can skip the second stage of that process entirely as they allow you to easily convert the Figma website designs into functional web page layouts.

There are a few great plugins that allow you to do just that for creating WordPress themes. We’ll talk more about those in a moment but first, let’s find a great-looking Figma website design template.

Where to Find Figma Website Design Templates

If you don’t plan on designing a website from scratch, the easiest way to design a website in Figma is to use a pre-made template.

These Figma website design templates come with complete page layouts and structures in a well-organized manner, allowing you to simply edit, customize, and instantly convert them into WordPress themes.

These are some of the best places for finding Figma website templates.

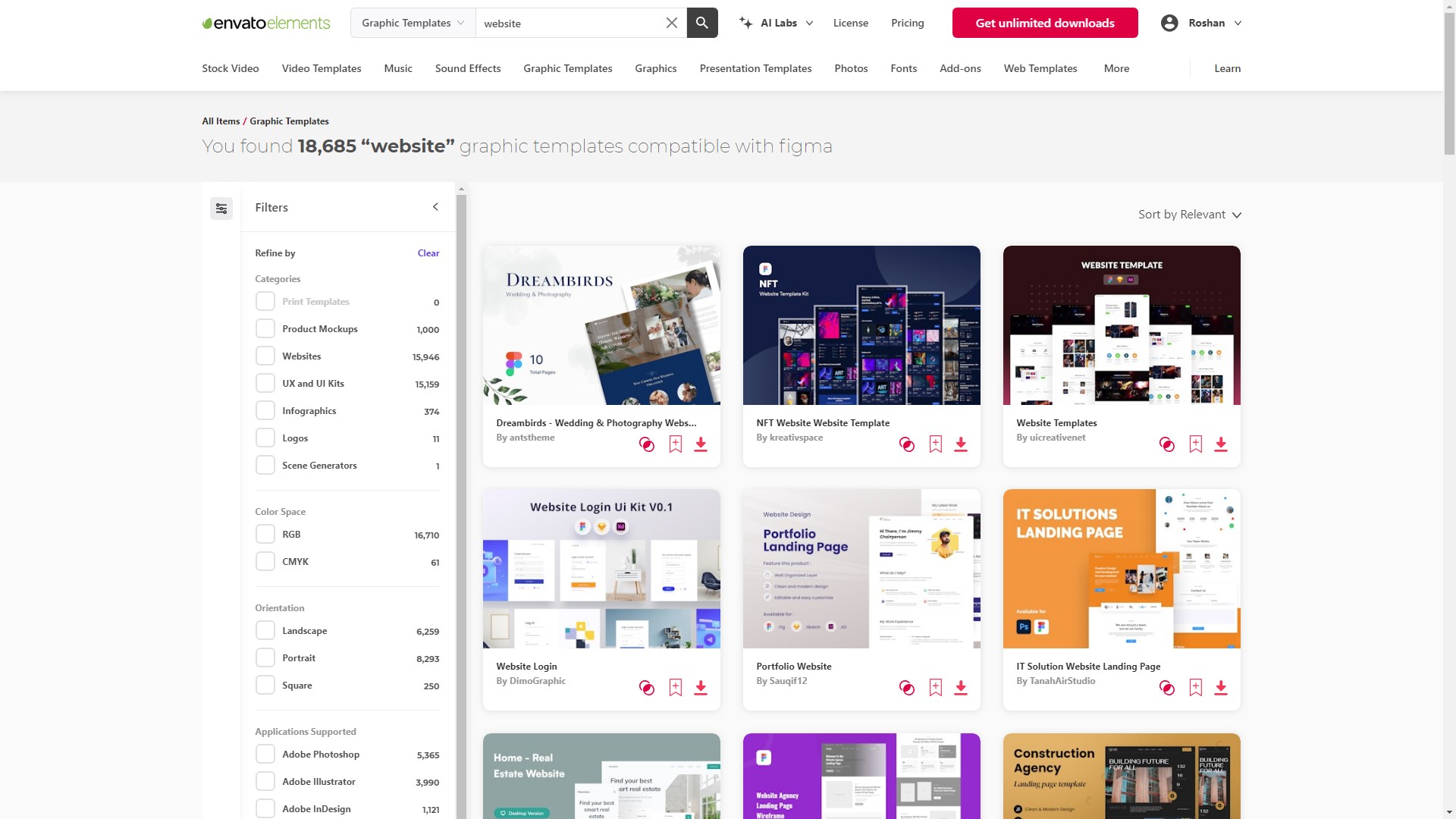

Envato Elements

Envato Elements has a massive collection of thousands of Figma website templates. This collection includes designs for all types of websites from marketing landing pages to blogs, magazines, and business websites.

Envato Elements also gives you unlimited access to the platform for a single price. When you subscribe to the platform, you will be able to download as many templates as you want and use them in your commercial projects without hesitation.

Creative Market

Creative Market also has a great collection of Figma templates, including website design templates for eCommerce websites, sales pages, travel websites, business sites, and more.

If you’re only looking for a Figma website template for a single project, Creative Market is most suitable for your project as it allows you to buy templates individually.

Figma Community

For those of you working on personal projects and learning to use Figma, the official Figma community has lots of free website design templates you can use to experiment with. These templates are free to use but come with limitations. But they can be a great resource for learning.

You can also check out our curated collection of the best Figma website templates to find our top picks.

Best Figma-to-WordPress Plugins

The second step of the process is finding the right Figma plugin to convert your website design into a functional theme. These are the top plugins you can use for the job.

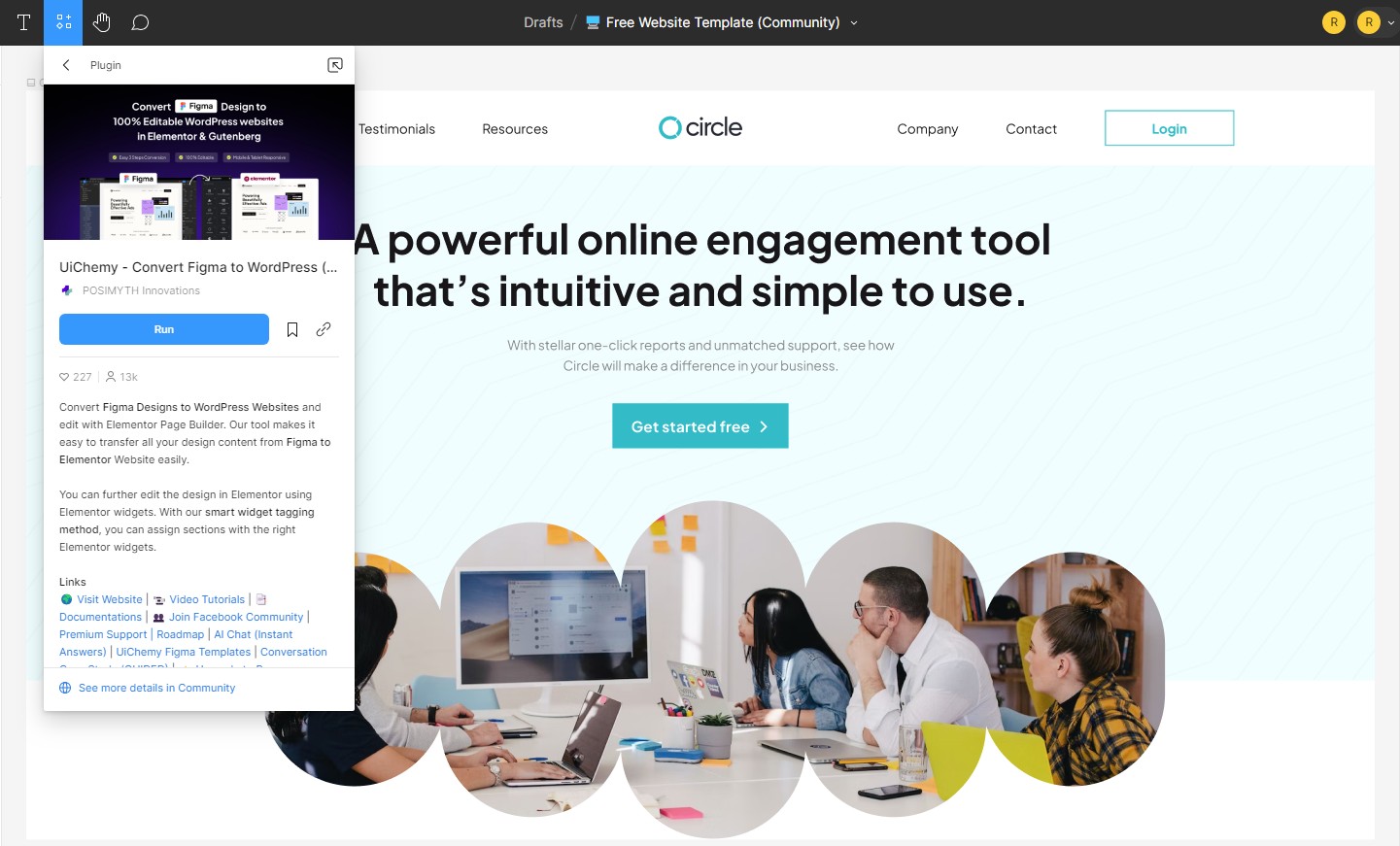

1. UiChemy

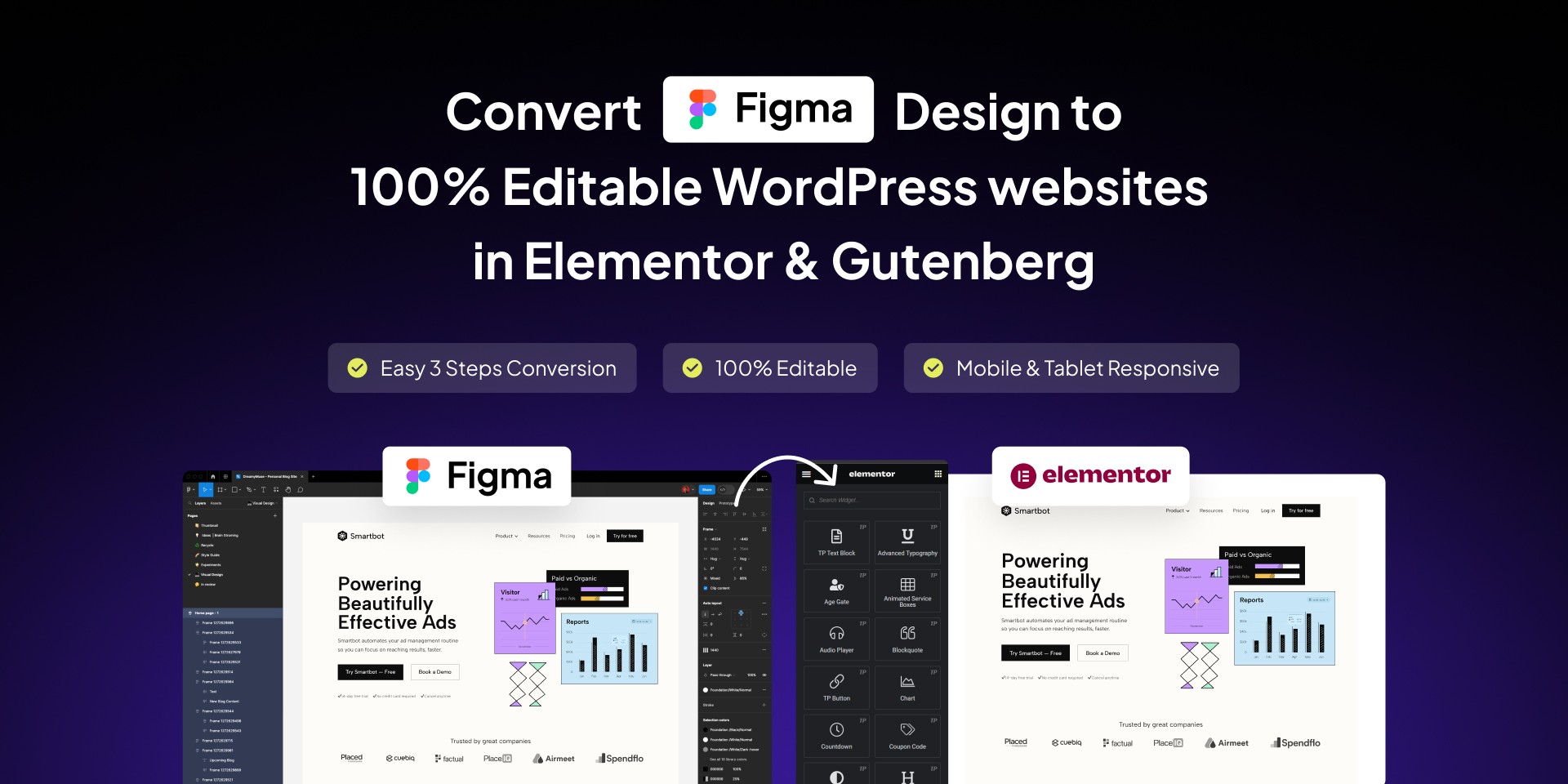

UiChemy is arguably the best choice for converting your website designs into WordPress as it uses the Elementor page builder for the transformation process. And the developers are working on adding support for the Gutenberg editor as well.

This will make it much easier for you to customize the design once it’s transformed into WordPress theme format. If you want to add more items to a page, you will be able to do so using the Elementor drag-and-drop editor. The entire process is code-free!

UiChemy has a free plan that lets you use the plugin for up to 10 exports per month.

2. Fignel

Technically, Fignel is not a Figma app. It’s actually a web app that lets you convert Figma designs into WordPress themes. This tool is simpler and easier to use than Figma plugins and it’s much more beginner-friendly as well.

All you have to do is copy the share link to your Figma design and paste it into the Fignel app to transform the design instantly into WordPress. It’s that simple!

Fignel is currently in Beta and you can try it for free.

3. Yotako

Yotako is another Figma plugin for turning your Figma website designs into WordPress theme designs. This plugin is more suitable for making more complex and sophisticated websites with multiple pages.

Yotako is a premium plugin and you’ll need to subscribe to its $30 per month plan to use it. Or you can export a single design for a one-time fee of $20.

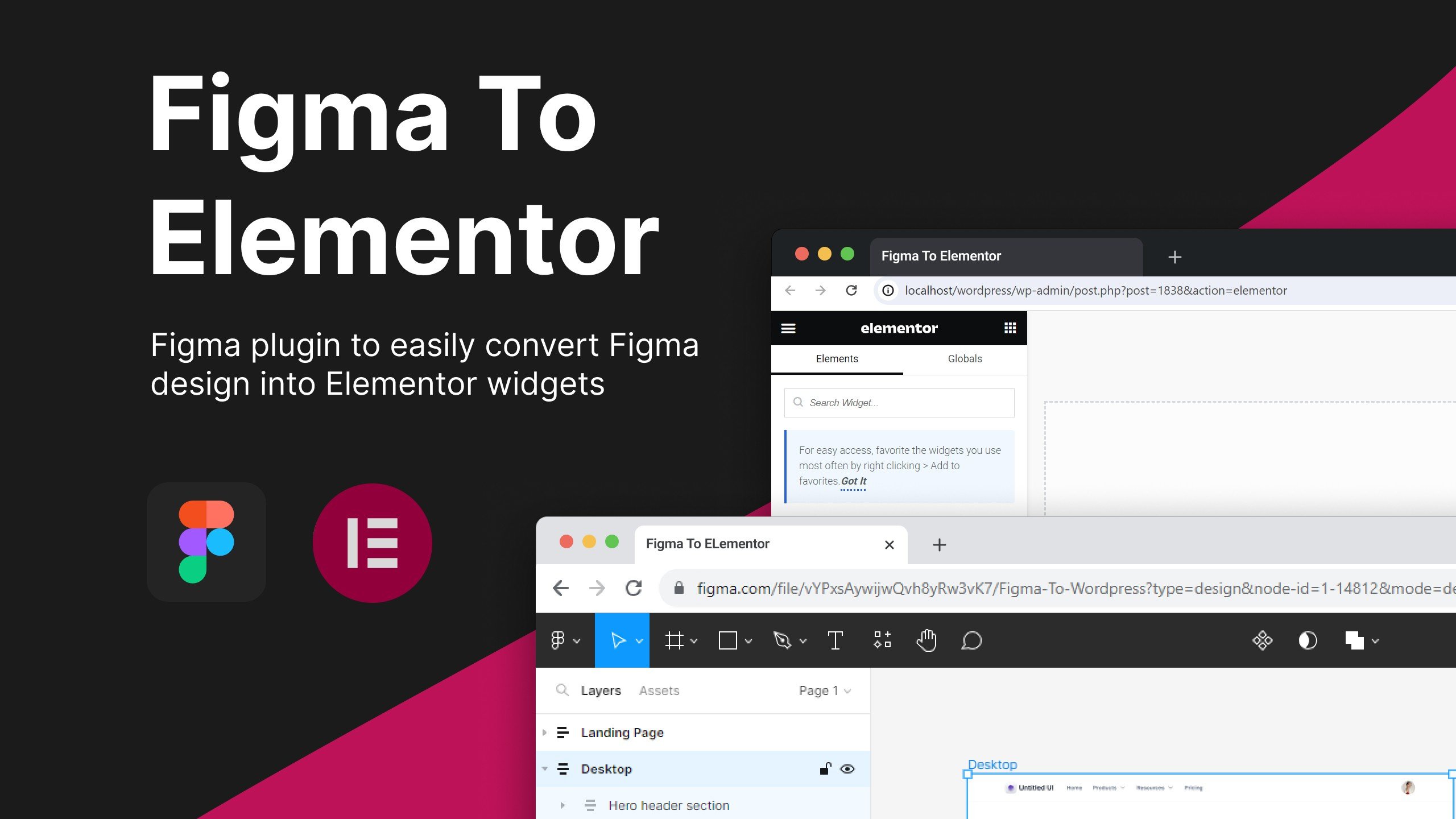

4. Figma To Elementor

This Figma plugin is developed by a community member as a free solution for users to convert their design into WordPress format. It also uses the Elementor page builder and you can easily edit the design even after converting it.

The plugin is free to use but it requires a more sophisticated process to set it up. And the results it generates are not always perfect so it’s most suitable for speeding up your coding process.

5. Figma To WordPress Block

This Figma plugin is also created by the same developer behind the Figma to Elementor plugin. It also features a similar process of converting Figma designs into WordPress. However, when using this plugin, it will generate code that you can paste directly into the WordPress Gutenberg block editor to create your page designs.

How to Convert Figma Design to WordPress Theme

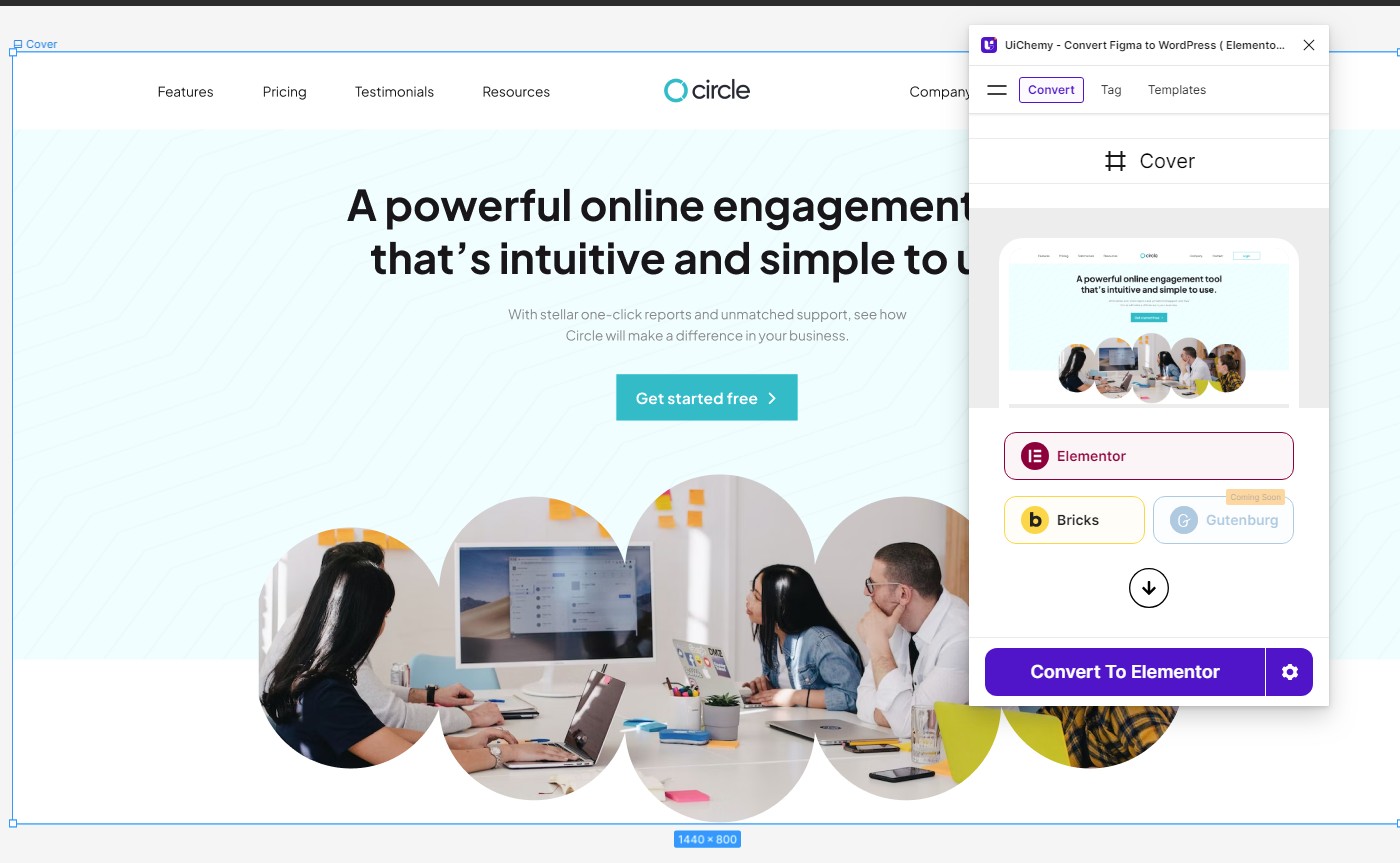

To show you how easy it is to create a WordPress theme using Figma, we did a quick demonstration using the UiChemy plugin. Here’s how it works.

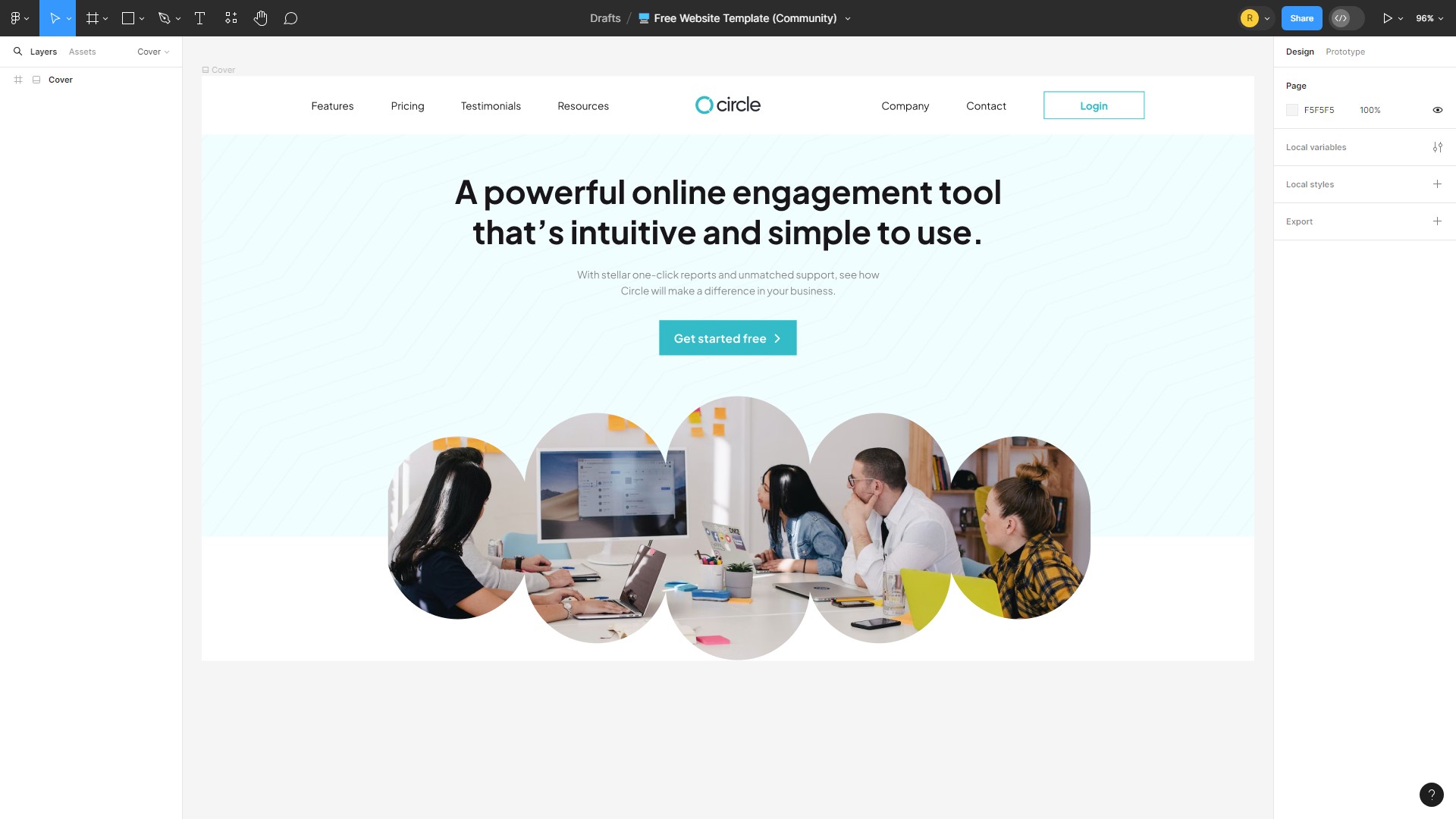

Step 1: Open the Design

First, open the website design in Figma. Make sure it only has the designs you want to convert to a WordPress theme.

Step 2: Run the Plugin

Run the UiChemy plugin and select your opened website design page.

You will be prompted to activate the plugin. Sign up for a UiChemy account (it’s free) and get a serial key to activate it.

Step 3: Generate the Theme

Select and assign the elements of the website layout correctly. Then click the Convert to Elementor button to transform the design into WordPress format.

Once complete, you can download it as a JSON file to import into Elementor page builder or Live Import to WordPress to start editing right away.

For a more detailed guide, check out this video tutorial.

Using a plugin is the easiest way to convert a Figma website design into a WordPress theme. However, if you prefer to do things manually, you can do so using a WordPress website builder like Elementor or Divi Builder. This free course on YouTube will show you how that process works.

Tips for Achieving Best Results

Here are a few tips to help you effectively use Figma plugins and templates to design and build a WordPress theme.

1. Use a WordPress UI Kit

Look for a Figma WordPress UI kit that includes elements commonly used in WordPress themes, such as widgets, buttons, and form styles. This ensures consistency across your design.

2. Customize Templates Thoroughly

Make sure to customize the template to fit your brand’s identity and the specific needs of the site. Adjust colors, fonts, and layout structures to make the design unique.

3. Utilize ‘Content Reel’ for Realistic Mockups

Use the Content Reel plugin to populate your designs with realistic text, images, and other media. This gives you a better idea of what the final product will look like.

4. Responsive Design with ‘Autoflow’

Use Autoflow to connect different frames and layouts in Figma to visualize the navigation flow. This is crucial for ensuring a seamless user experience across all device sizes.

5. Design for Extendability

When designing components and elements, think about how they might be used or altered in the future. Using Figma’s component system can help ensure your design is flexible and easy to update.

6. Prototype Within Figma

Before moving your design into WordPress, use Figma’s prototyping features to test user interactions and flow. This step can help identify any usability issues that need to be addressed.

Conclusion

Keep in mind that these Figma plugins and tools may not work perfectly every time. They are meant to help speed up your workflow and make your job easier, not to replace you as a web designer.

You will have to do some work manually to get them to function properly. But it will be a lot less work than designing and coding a WordPress theme from scratch.