30+ Best Android Phone & Tablet Device Mockups (Free & Pro)

When showcasing an app or a website design, it’s important to use the device mockups that represent the right platform. Never make the mistake of using an iPhone mockup to present an Android app design.

Most designers often use iPhone mockups to showcase their designs. But, if you want to make a bigger impact with your presentation, you should use an Android mockup because Android has the highest mobile market share. It will allow you to relate to a bigger audience.

We handpicked a collection of amazing-looking Android phone mockups and tablet mockups you should use for your next project. You’ll find the latest Samsung device mockups, including the Z Flip and G Fold. Along with many others.

Explore all the mockup templates below, there are a few free mockups in there as well.

2 Million+ Product Mockups, Templates & More With Unlimited Downloads

Download thousands of beautiful product mockups (for both physical products and devices), to showcase your digital or physical design with an Envato Elements membership. It starts at $16 per month, and gives you unlimited access to a growing library of over 2,000,000 mockups, design assets, graphics, themes, photos, and more.

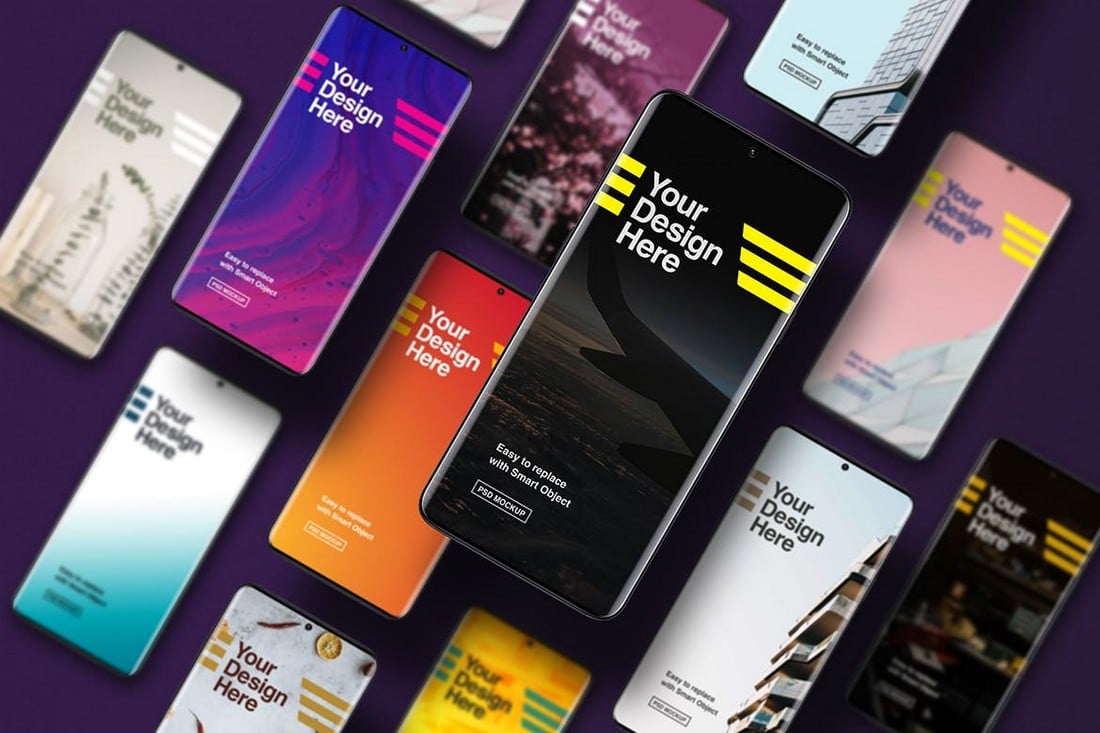

Android Smartphone Mockup

This Android phone mockup is perfect for putting your designs in the spotlight. It features a very elegant and modern scene where you can present your designs in a professional way. You can even change the colors using color layers. And place the designs on the mockup using smart objects.

Black Android Smartphone Mockups

Featuring the latest Samsung smartphones with curved edges, this mockup is the ideal choice for showcasing app screens. Everything in this mockup, including the shadows, light, and background can be easily customized to your preference. All objects are isolated.

Android Phone Sketch Mockups

If you use the Sketch app for your designs, this set of Android mockups will come in handy. It features 3 different mockup scenes in Sketch file format. You can edit and customize the mockups however you like.

Android Phone Mockup Set

Another beautiful mockup scene for showcase app screens. This mockup allows you to show off multiple screens of features of your apps and websites at the same time. And it’s perfect for portfolio presentations as well.

Galaxy Z Flip Mockup Templates

This bundle comes with 5 different mockup scenes featuring the new Samsung Galaxy Z Flip phone. With these mockups, you can present your designs with a unique approach and make your presentation stand out. Each PSD file includes smart objects for easily placing your design.

Free Android Phone Mockup PSD

This free and minimal Android phone mockup features a very simple design. It’s perfect for showcasing your designs in a modern environment. The mockup is free to download and keep.

Free Android & iOS Device Mockups

Facebook has designed a massive collection of device mockups that designers can download free of charge. It includes phone, tablet, and desktop devices from all kinds of brands from Apple to Google, Samsung, and more.

Galaxy Tab S7 Mockups – 50+ Scenes

Finding professional-looking tablet mockups for Android is not an easy task. Which is why you should download and always keep this bundle on your hard drive. It includes 51 different mockup scenes featuring the Samsung Galaxy Tab S7. All mockups look very realistic and beautiful.

Creative Android Smartphone Mockup

This bundle includes 11 different mockup scenes featuring Samsung S10 phones. Each mockup also includes elevated screens that make the mockup look creative and advanced. It’s perfect for showcasing different features of apps. You can easily change the colors of the mockups as well.

Multipurpose Android Smartphone Mockup

A perspective mockup scene for presenting multiple screens of your designs in one place. This mockup can be easily customized with smart objects and it works as a cool background for websites and landing pages as well.

Samsung Galaxy S20 Mockup

Looking for a mockup template in super high resolution? Then you’ve found it. This mockup not only features the latest Samsung Galaxy S20 but also comes in 12K resolution. The template features editable shadows, changeable backgrounds, and smart objects.

G Fold Smartphone PSD Mockup

The new Samsung G Fold is not quite popular yet but it’s perfect for showing off your apps and website designs with a futuristic vibe. This template features an easily editable and resizable device mockup of the G Fold.

Free OnePlus 6 Android Phone Mockup

This free mockup features a OnePlus smartphone with a high-quality front-facing view. It’s ideal for showcasing your Android app designs and screens. The template comes in a fully editable PSD file.

Free Android Phone Mockups with Hand

A collection of 7 Android phone mockups you can download for free. It includes mockups that show the devices being held by a hand. The templates have editable backgrounds as well.

Surface Pro Tablet Mockup

Technically, Surface Pro is not an Android tablet as it runs on Windows. But still, it’s a great device for presenting website and app designs. This mockup in particular features a beautiful scene. It comes in PSD format with organized layers.

Samsung S20 Ultra Mockup Template

This mockup features the new Samsung S20 Ultra device. It includes both front and back views of the device and it’s available in black and gray colors. The mockup is most suitable for presentations on websites and portfolios.

Samsung S7 Tablet Mockup

If you prefer to showcase your designs in perspective view, this Samsung Galaxy S7 tablet mockup is perfect for you. It includes both front and back views of the mockup in a perspective scene. You can also change the background as well.

Android Smartphone Mockups – Front View

This mockup template comes with a trio of Android smartphones with front-facing views. They are ideal for showing off app screens on landing pages and websites. You can also edit the shadows and change the backgrounds to your preference.

Samsung Galaxy S20 Mockups – 13 Scenes

A collection of high-quality Android device mockups featuring the Samsung Galaxy S20. There are 13 different scenes in this bundle featuring fully customizable designs. You can change the device colors and backgrounds as well. The mockups are available in 4K resolution.

Elegant Android Smartphone Mockups

This is a set of Android smartphone mockups that feature very elegant scenes with luxury vibes. There are 5 different mockup scenes in this pack, including one showing the device being held by a hand. It features the latest Samsung S21 Ultra smartphone.

Free Minimal Android Phone Mockup

A minimalist phone mockup you can use to present various types of designs. This mockup is completely free to use. And it’s ideal for showing off designs on your personal portfolios.

Free Xiaomi Mi MIX 2 Mockups EPS & PSD

Another free Android mockup featuring a phone from the Xiaomi brand. This mockup comes in EPS, PSD, and Illustrator file formats. You can edit and customize it however you like.

Clay Android Smartphones Mockup

Clay-style mockups are perfect for showing off different types of apps as they don’t feature any branding. This clay phone mockup is completely editable. You can change the device colors as well as the background.

Samsung S21 Ultra Mockup Kit

With this set of Samsung S21 mockups, you’ll have plenty of choices for presenting your designs. There are 24 different mockup scenes to choose from. All come in high-resolution PSD files.

Samsung Z Fold 2 Mockup

A set of stylish Z Fold device mockups. This bundle includes 5 different mockup scenes featuring the Samsung Z Fold 2 in various views and angles. They feature smart objects as well.

Samsung Galaxy Z Flip Mockup

This bundle includes a set of Galaxy Z Flip mockups featuring the device in the fully expanded open position. The mockups are available in multiple file formats, including Adobe XD, Sketch, and Figma.

Samsung Galaxy Watch 3 Mockups

Grab this bundle of Galaxy Watch mockups to showcase your smartwatch apps in style. This pack includes 24 different scenes in easily editable PSD files with smart objects.

Application Screen Phone Mockup

This is an advanced, and easy-to-edit mockup. It contains everything you need to create a realistic look for your project. It guarantees a good look for bright and dark designs and provides easy navigation, well-described layers, friendly help file.

Tablet & Smartphone Mockup

This is an easy to edit mockup featuring both a tablet and a smartphone with customizable displays that you can use to showcase your app, website, or game. You can move both devices inside the scene, disable either one, adjust shadow opacity & color, change the background color or replace the background entirely with your own.

Android App Screen Mockup

This app UI / phone screen mockup is created for UI/UX designers, which can help them present their design look good. This app UI mockup is created with photoshop Smart object; easy to use even for a beginner in Photoshop.

S22 Phone Mockup

Present your app design, game design, UI/UX design, Instagram post and story and templates with this set of 11 Samsung S22 phone mockups included! Simply place your design with a single click using the Photoshop smart object. It’s really that simple!

Looking for iPhone mockups? Then check out our best iPhone mockup templates collection.