30+ Postcard Mockup Templates (Free & Pro)

Regardless of whether you’re designing a postcard for travel and tourism or business and marketing, there’s no denying that everyone loves receiving one of those small colored cards in the mail – as long as it looks good, of course! But how to make sure your design will look as good in someone’s mailbox as it does on your computer screen?

Mockups are the answer, and we’ve done the research for you and rounded up the very best postcard mockup templates from a range of graphic design sources.

We’ve included both free and premium options with a range of different styles and designs, to make sure there’s something for everyone – and they’re all ready to download instantly.

Design Your Own Postcard Mockup in Seconds

Why settle for one postcard mockup template when you have access to thousands of different kinds of stationery mockups for just one price? Plus, you can edit all these templates online, without ever needing to use Photoshop.

That’s exactly what Placeit does. It lets you use high-quality mockups, edit them using its online editor, place your own designs, and download them quite easily. No need for Photoshop. And yes, it includes loads of postcard mockups too, in all sorts of settings. Think of it as a postcard mockup generator. But of course, it’s more than that.

Fresh Vintage Postcard Mockup Template

First in our list of postcard mockup templates is this vintage-inspired, premium layout from Placeit, showcasing your postcard design surrounded by rugged brown paper, pens, leaves, and a pair of glasses. The photo and background colors can both be customized, and you can also add your own graphics.

Wooden Surface Postcard Mockup Template

The perfect choice for a classy and minimalistic design, this postcard mockup template features two postcards lying on top of a dark wooden surface. It’s simple enough to let your postcards be the focus, but the texture of the wood adds a level of interest that really makes your designs stand out.

Festive Postcard Mockup Template

Looking for a high-quality postcard mockup template for a Christmas-themed card? Look no further – this premium festive option from Placeit is a winner, and will showcase your design proudly in the middle of a range of Christmas-inspired decor, including gifts, pinecones, and a decorative snowflake.

Plain Double Postcard Mockup Template

Another popular minimalistic option, this premium postcard mockup template from Placeit displays two postcards against a plain background, allowing you to customize both the background color and the two cards to fit in with your branding and aesthetic. You can also add custom graphic elements to make the design your own.

Vintage Photography Postcard Mockup Template

Our next postcard mockup template is brilliant for any photography themed project, or for a postcard that calls for a retro vibe. This high-quality layout features your postcard design on an old wooden desktop, next to a vintage camera and a pile of worn-looking paper.

Simple Three Postcard Mockup Template

This set of three PSD postcard mockup templates is a popular choice for all kinds of businesses to display their postcard designs, due to it being highly customizable and able to feature three different designs in a single mockup. It’s a great option if you’re designing more than one postcard for your project.

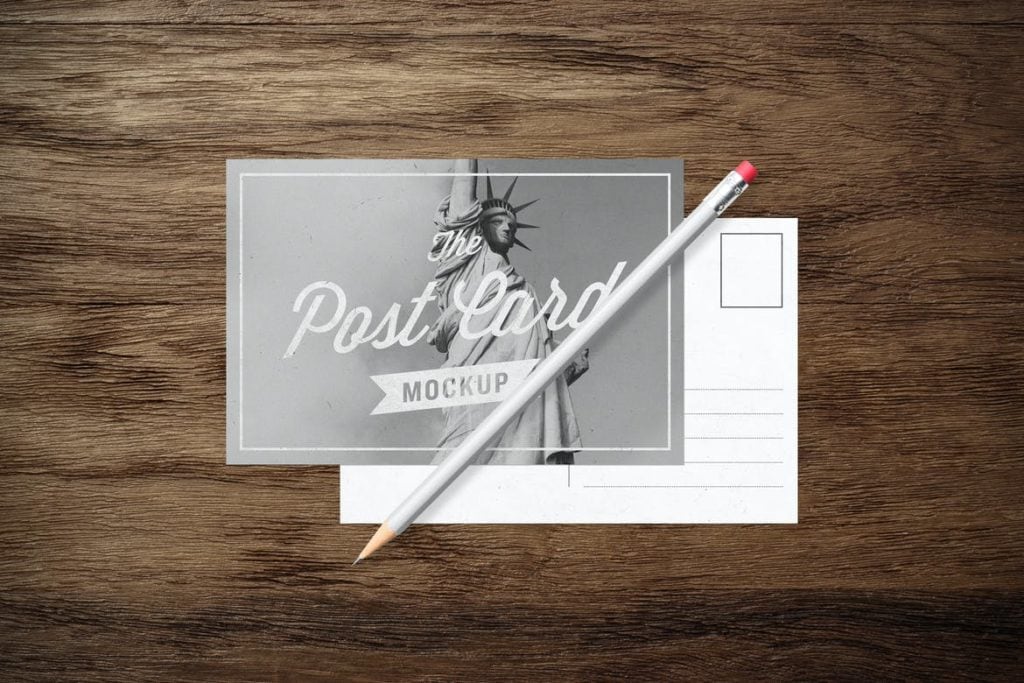

Pencil Postcard Mockup Template

Next in our lineup of the best postcard mockup templates is a highly versatile and customizable layout that allows you to move around the two postcards, as well as move or get rid of the pencil that’s featured as an additional vector graphic. You can also edit the background as required.

Coloured Wall Postcard Mockup Template

This stunning postcard mockup template showcases both a landscape and a portrait postcard leaning against a colored wall that contrasts against the stone floor, for a beautiful retro look. It comes as a high-resolution PSD file, and is available for free download from Design Hooks.

Portrait Postcard Mockup Template

Another option that features the less common portrait orientation, this desktop themed postcard mockup template is a modern and clean way to showcase your design. It features five high quality, fully layered PSD files, each with photo filters, smart objects and a range of decorative elements such as wooden pencils and a lush green pot plant.

Graphic Desktop Postcard Mockup Template

Next up is this elegant premium postcard mockup template from Envato Elements, featuring back and front views of your postcard in the center of a dark, textured surface, surrounded by graphic design tools and other decor items. This template also includes photo filters and smart objects, making it super easy to customize.

Hand Holding Postcard Mockup Template

Here we have a simple yet effective postcard mockup template where your design is displayed being held up by a woman’s hand against a plain, neutral background. The use of shadows and focus effects give this template an ultra-realistic finish, and it’s versatile enough for any kind of postcard design or color scheme. Plus, it’s free!

Minimal Envelope Postcard Mockup Template

Here we have a gorgeous, simple postcard mockup template from Envato Elements featuring your postcard next to a plain white envelope against a customizable background. Every element of this mockup can be adjusted to suit your needs, and the PSD file includes well-organized layers to make it even easier.

Folded Postcard Mockup Template

A simple and elegant option, our next postcard mockup template is a free download that incorporates a folded version of a postcard into a photorealistic layout featuring a plain background and a gorgeous marble tile for added interest. Each layer can be fully edited or removed, and the quality is second to none.

Floral Postcard Mockup Template

Our next premium postcard mockup template is a modern, chic set of six layouts featuring romantic floral elements and cute stationery items against a neutral, textured background that will really make your designs come to life. You can choose from a range of shadows and filters to customize each mockup.

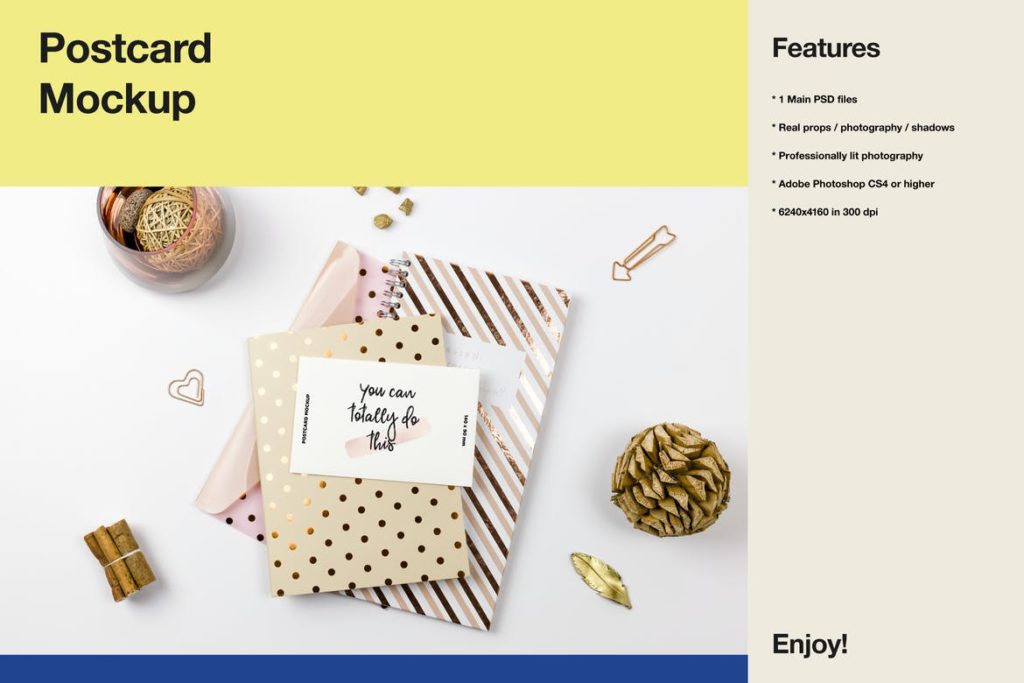

Stationery Postcard Mockup Template

Another premium option from Envato Elements, this postcard mockup template is a sweet, feminine arrangement of crafty stationery supplies and pastel-toned paper items to complement your postcard design. It features a high resolution and smart object layers for a professional and clean result.

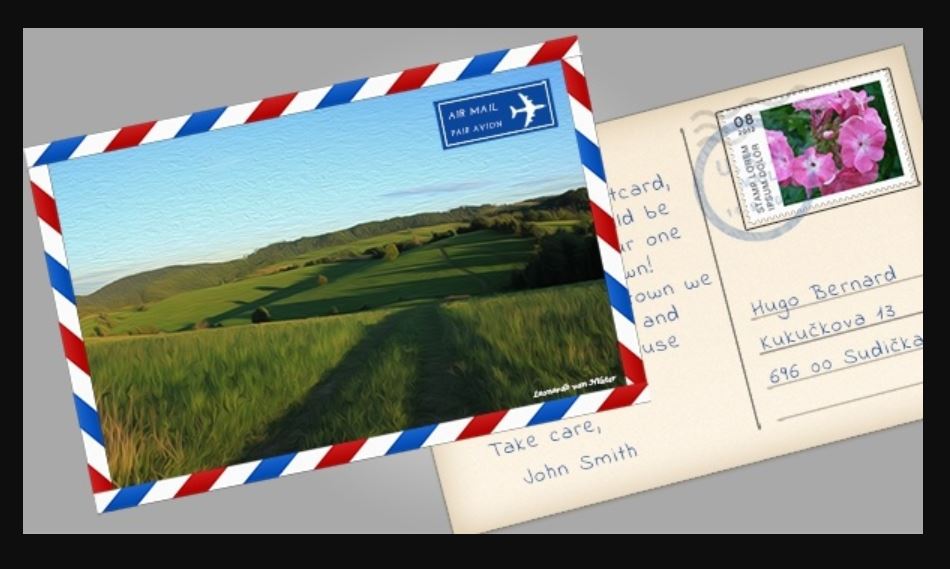

Classic Postcard Mockup Template

Here we have a classic postcard style mockup featuring a simple layout that allows you to display both angles of your design, complete with the iconic red, white and blue stripes and an authentic-looking Air Mail stamp to give it a realistic look. It’s the perfect choice if you want a minimal design with a slight vintage feel.

Closeup Postcard Mockup Template

It’s all in the details with our next postcard mockup template – this geometrically inspired option will showcase your postcard in a series of close-ups, and ensure that the focus is entirely on your design! It includes a single PSD file featuring smart objects, well-organized layers, and customizable colors and textures.

Floating Postcard Mockup Template

Get carried away with this unique postcard mockup template featuring two floating postcards, designed for you to include both the front and the back of your creation. The use of shadows and wall coloring gives this mockup a pseudo-realistic effect, and it’s available as a free instant download.

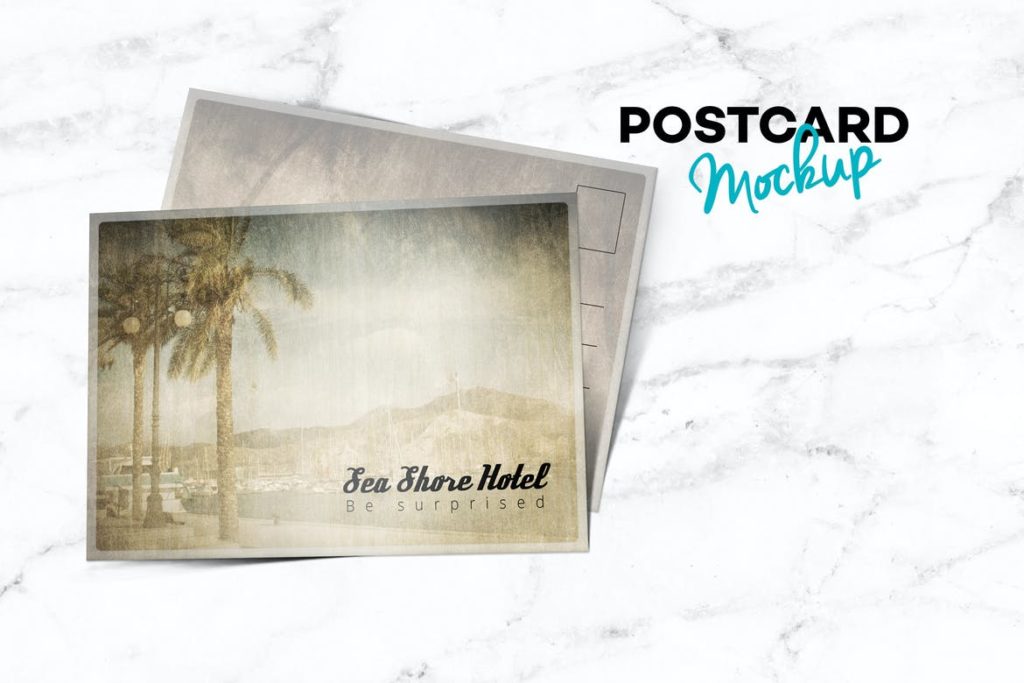

Marble Postcard Mockup Template

If you’re looking for a simple yet chic postcard mockup template, consider this stunning set of five premium mockups from Envato Elements, featuring an isolated marble background that can be easily changed, realistic folds and shadows, and fully movable and editable objects.

Shadow Postcard Mockup Template

The next of our postcard mockup templates is this beautiful premium design featuring your postcard sitting atop a cylindrical stage, against a plain background with dramatic shadows overlays. Each aspect of this high-resolution mockup is customizable, from the background colors to the shadows.

Free Postcard & Envelope Mockup Template

Send your love all over the world using Adobe Photoshop and edit not only the highly realistic postcard and the envelope but also their background. The layered mockup designed in 5400 x 3750 pixels resolution at 300 dpi is also accompanied by a free help file with tips and tutorials.

7×5 Postcard Mockups

These 7×5 postcard mockups are the best to showcase your latest greeting, mailing, post and corporate branding designs. You can use its smart object feature to add your own design with a single click. Moreover, you can also customize the color, effects, shadows and background as well.

Square Postcard Mockup Template

This styled pack contains 4 square postcard mockups and 4 styled photos that are perfect for you to use for your website, social media & digital marketing. You can easily replace the artwork with the smart object, use your favorite filter and post on Instagram and Facebook or use for your website as a hero header/blog post.

Wedding Postcard Mockup Template

Use the smart layer object to drop your designs. Simply paste your design into a smart object and save it. Each file has a Safety zone for a smart object inside so that it is more convenient for you to place objects.

Simple Postcard Mockup Template

Showcase your design, illustration, branding or even a custom stamp design using this easy to edit postcard mockup template!

You can edit the front, back and even the stamp design independently using the 3 smart object layers inside the PSD file but note that the back and front view are stuck together in order to preserve the realism of the shadows interacting between the objects and the background.

Photography Postcard Mockup Template

Sometimes it is hard to understand how to present your design. If you are stuck in such a situation, these postcard mockups are a perfect choice for you! Just insert your artworks inside the Smart Layer and you are done!

Designer Postcard Mockup Template

A fully layered postcard template will help you present any postcard design! And this mockup enables you to do it in a photorealistic way. Just drag and drop your artworks inside the Smart Objects and it will do the rest. The PSD file is compatible with Photoshop, so you won’t need any other software.

Christmas Postcard Mockups

Create a beautifully designed Christmas card with care and love so no one will want to throw it away. The background of this postcard mockup and design color can be customized easily with just one click, so start creating right now!

Elegant Postcard Mockup Template

Here comes a highly realistic postcard mockup template that will surely become a part of your projects! It is both beautiful and functional: all you have to do to get the result you were craving for is put your artworks inside the Smart Layer included.

Minimal Postcard Mockup Template

Do you want your postcard design to give off an elegant, heartwarming vibe? Then check out this PSD mockup. Horizontal envelope and postcard mockup template can help you create a realistic presentation of your next project. Just place your artwork or text inside the well organized Smart Layers and in a few seconds you’ll get the result.

And with that, you have a range of professional postcard mockup templates to choose from for your very own project. Free or premium, classic or quirky, there’s something for every kind of design here – and you’re only a quick download away from bringing your postcard to life.